Stephanie Eichberg

No doubt, Vienna is a beautiful city and one doesn’t really need a specific reason to go and spend a few days in the vicinity of world-famous coffee houses (marvellous cakes, too!); brilliant art (Klimt, Kubin, Stifter…); architecture (the Martinellis, Otto Wagner, Hundertwasser…) or opera houses.

But the reason why we chose it as the destination for this year’s History of Medicine Field Trip is because a number of individuals discussed in our modules had made their first appearance in Vienna: the late eighteenth-century physician Anton Mesmer whose unconventional treatment influenced the history of hypnosis; the phrenologists Franz Joseph Gall and Johann Spurzheim; Sigmund Freud; Ignaz Semmelweis, the pioneer of antiseptic procedures – just to name a few. As it turned out, the richness of Vienna’s medical heritage exceeded our expectations by far.

What follows is a synopsis of things we learned and things we looked at, including some unofficial titbits of information that our wonderful museum and tour guides shared with us over the course of our visit.

MONDAY, 11th FEBRUARY

Our first point of contact with Vienna’s medical history was the Josephinum, a beautiful building specifically designed to house Vienna’s new faculty for surgery and medicine, which was commissioned by the Habsburg Emperor Joseph II in 1785.

The Josephinum, then and now: http://www.josephinum.meduniwien.ac.at/home/museen/museums/en/

Prof. Sonia Horn, who is in charge of the historical collections at Vienna’s Medical University, gave us an overview of this unique institution and its historical development, which was followed by a tour of the History of Medicine Museum. The Josephinum’s history provides fascinating testimony to a once close connection between medicine, society and the state, due to Joseph II’s keen interest in medical reforms. Another outcome of the Emperor’s involvement in Vienna’s medical matters is the world’s second-largest collection of wax anatomical models held at the Josephinum. Only four of such collections have survived in Europe, the largest being La Specola in Florence, home to the creator of the models, the Italian wax sculptor Clemente Susini (1754-1814). Joseph II himself had visited Florence in the 1780s, his personal surgeon in tow, and after seeing the spectacular creations of Susini, he immediately ordered a large number of anatomical models for Vienna’s medical faculty. Interestingly, when the wax models arrived in Vienna (a total of 1192 specimens, delivered over two years ‘on the backs of mules and men’[1]), the medical establishment was markedly less impressed than their Emperor. In a recent article of the subject, Anna Maerker concludes that, rather than being hailed as useful models for teaching anatomy to medical students, they actually sparked debates on their utility, resulting in conflicts between surgeons and physicians. Overall, they were mostly perceived as ‘toys’ to entertain the public.

We certainly found them entertaining. The wax figures are so eerily beautiful that they alone would have been worth the visit to Vienna. Apart from stunningly detailed wax preparations for individual organs, including the vascular, muscular and nervous system, and manifestations of diseases with varying levels of grossness, the stars of the show are the life-sized anatomical figures lying or standing in their original caskets made of rosewood and Venetian glass. With their classical postures inspired by early modern anatomical textbooks, the male wax figures in particular appear to have stepped directly off the pages of Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica, only to freeze again in their respective poses.

The most famous one, however, is the Anatomical Venus, the wax figure of a female lying in a glass casket like in a coffin, almost lasciviously splaying out her viscera to the observer. She is often compared to Snow White or Sleeping Beauty because of her princess-like pose (though I don’t know about that, unless I’ve been missing out on the original Grimm’s version in which the heroines are dismembered at the end of the fairy tale…). Her waving hair and eyelashes are made from real human hair, and one of the most interesting titbits of information we were fed by our guides was that cultural preferences in female beauty appeared to have been well catered for: while her Florentine counterparts are all brunettes, the Viennese waxen Venus is blond. It made us wonder whether all Venuses made for the north of Europe would have been furnished with blond hair, while those heading for the south were brunettes, or whether Joseph II requested this particular detail when he placed his order (no cultural differences or preferences are discernible in the male figures whose bodies are all flayed to reveal the vessels, muscles and nerves). One of our helpful guides further speculated that the pearls round her neck and/or the gold band in her hair might have been added by 19th–century medical students for a joke. We could well imagine the impact this naked and revealing beauty had on a bunch of unruly male students…. Our (well-behaved) IBSc students at least marvelled at the anatomical detail and accuracy, and one of them remarked that he would have welcomed the use of such models in his own anatomy courses at UCL. Images in books, computer models and even real corpses were, to his mind, not able to convey the rich detail and intricate beauty of the human body in the same way as these models did. One can only agree.

Viewing afterwards the beautiful library and an extensive medical instrument collection, we all felt a little dizzy when we left the Josephinum. So much to see and take in! I’m not sure our brains could have handled another two or three hours of information overload; as it was, our planned tour to the Museum for Forensic Medicine fell flat, due to illness of our tour guide….so we went instead to the nearby campus of the medical university, indulging in a hearty Austrian meal and beer from a monastery brewery.

TUESDAY, 12th FEBRUARY

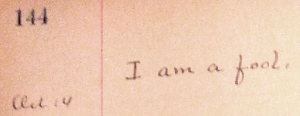

Figure 1: A model painting of the Old Hospital Campus in the 1780s. The layout is not accurately presented, due to the addition of several yards over time. Figure 2: The ‘Narrenturm’ (Fools Tower). Figure 3: Inside the Fools Tower. The former cells are now used as storage space for additional specimen from the anatomical-pathological collection.

http://www.viennadirect.com/sights/hospital.php

For Tuesday, we had booked a tour of the Fools Tower, which is situated next to the grounds of Vienna’s old General Hospital (today’s university campus) and which now houses a large anatomical-pathological collection. Stomping through the snow, our guide led us first through the vast labyrinth of the old hospital campus. The hospital buildings are organised around several yards which are connected via gate passes. It is hard to believe that this amazingly organised hospital structure with its several yards for different diseases dates back to the 18th century (the first hospital building was erected in 1693). It is easy to get lost in these grounds, but the underlying idea of separate, yet connected yards is genius: functioning like wards in a modern hospital, there would have been a yard for lung diseases, say, one for skin diseases, one acting as an obstetrics hospital with an adjacent orphanage (to discourage infanticide, women could enter through a separate gate, the ‘Schwangerentor’, give birth anonymously and leave their children at the orphanage), etc. What we found especially interesting was that the porter, sitting at the main entrance to the hospital, would assess incoming patients’ symptoms and then send them off to specific yards, implying that 18th-century hospital porters, although not members of the medical personnel, were the first link in the chain of medical diagnostics.

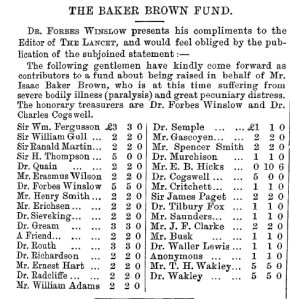

In the 19th century, the old hospital took on important research functions; illustrious names like Ignaz Semmelweis, Theodor Billroth (founder of modern abdominal surgery), Karl Landsteiner (discovery of blood groups and the Rhesus factor), all made an appearance. We greatly appreciated that our enthusiastic guide would not simply rattle through the names of great men and their great discoveries but also mentioned the darker side of Viennese medicine, such as incidents of experiments on patients and the influence of Nazi ideology on some scientists whose statues still decorate the hospital grounds.

Eventually (being sufficiently frozen), we entered the Fools Tower, the first ever building on continental Europe to house and treat mental patients, courtesy once more of Joseph II who had the Tower built in 1784. Historians claim that the Emperor’s personal interest in the healing of the insane was based on his membership of the Knights Templar or Rose Crusaders. The latters’ alchemist and mystic numerology seems indeed written all over the Fools Tower: the round building has 5 floors and has a circumference of 66 ‘Klafter’ (old Viennese measuring unit). Each floor contains 28 cells and the roof additionally houses an octagon which Joseph II is said to have visited on a weekly basis. Our guide also told us that an atmospheric-electric or magnetic field exists at the site of the Tower which might have been identified and used in the treatment of patients at the time (the Tower also features the world’s oldest lightning rod). It is still debated whether the Fools Tower’s round-shape architecture is based on or inspired by the Benthamite idea of surveillance; yet, apart from the fact that there was no central observation point, the building probably just made it easier for doctors and nurses to do their ‘rounds’ (though it is also said that the round shape was a deliberate way of enabling non-violent inmates to walk endless turns without encountering a hindrance). Patients suffering from raging madness were on the top floor, those with the lightest symptoms, such as melancholics, were housed on the ground floor.

Overall, considering its importance in the history of mental asylums, Carole and I were a bit disappointed that hardly any exhibition space was devoted to this initial purpose of the building. An exception was one cell that still contained its original door with spy hole, and a tiny model of an 18th-century cell. All floors were otherwise devoted to a vast anatomical-pathological collection, including phrenological skulls and the collection of the Viennese physician and electro-pathologist Stefan Jellinek (1871-1968) who began to collect specimens and reports about lightning strokes and accidents with electricity in the 1890s. The specimens – waxen and otherwise – even made our medical students feel a bit queasy….

Figures 1-3. Specimen of the anatomical-pathological collection at the Fools Tower, 19th-20th century. Figure 4: Gents – be careful where you take a leak…Electrical Protection in 132 Pictures; ca. 1930s by the Viennese physician Stefan Jellinek.

Our guide was a passionate storyteller who threw in an extra hour for us – the 3 ½ hour tour was only once interrupted for a much appreciated serving of coffee and homemade (!) cake. The students loved every second of it!

On WEDNESDAY, 13th FEBRUARY – a bitterly cold day with harsh winds and lots of snow – we ventured on a guided history of medicine tour through Vienna’s city centre. Such is the rich medical heritage of Vienna that one can book a variety of medically-themed tours set up and organised by a cultural historian. (http://www.wienfuehrung.com/Medicine_Vienna.html) We had booked a mixture of ‘Barber-Surgeons, Physicians and Quack-Doctors in Old Vienna’ and ‘From the Plague Hospitals to the Modern Clinics’. Our tour guide was another passionate storyteller who appeared unfazed by the blizzard and dropping temperatures (though she kindly led us to a café midway through the tour to enable us to thaw…). She was brilliant, in that she did not focus exclusively on history of medicine topics but weaved in other cultural highlights of Vienna. Thus it was that we once stood opposite the still operating Knights Templars’ headquarters and we also caught glimpses of the beautiful Lipizzaner horses at the stables of the Spanish Riding School (first named in 1572, it is the oldest of its kind). At the Plague memorial, erected 1693, we heard entertaining folk tales about drunkards who woke up in plague pits, the constant ringing of church bells at plague times to keep the air circulating to expel the miasma from the town; the use of theriac, this most elusive and mysterious universal remedy containing all sorts of ingredients, including the fat of executed criminals (this we learned standing in front of Vienna’s old court pharmacy which still displays the original layout and interior). We were told that the early modern and slightly unorthodox physician and alchemist Paracelsus had completed part of his medical studies in Vienna (there is even a beer bearing his name and the Paracelsian inscription “Beer is a truly divine medicine”); that the Hofbibliothek, the former court and now national library, contains some of the oldest medical manuscripts, such as the 6th-century illuminated Materia Medica by Dioscorides and…. I could go on and on.

Vienna is so infused with medical history that a whole travel guide has been published on the subject – written by doctors for doctors (W. Regal, M. Nanut, Vienna. A Doctor’s Guide, 2007).

Figure 1: The Plague Column (1693) at the heart of Vienna’s city centre. Figure 2: Early modern physician in plague-protection attire. . Figure 3: The old Bürgerspital which became the first teaching clinic for medical students under Anton de Haen. Figure 4: Vienna – A Doctor’s Guide, a travel guide written by doctors for doctors.

http://www.wienfuehrung.com/Medicine_Vienna.html

On the same day – to make the most of this last afternoon in Vienna – some of us went to another eye-opening museum which is probably the only one of its kind worldwide: the Museum for Contraception and Abortion. Since related debates tend to focus mostly on the life and death of the unborn, this museum extends the focus by looking at the historical, political, international, cultural, and domestic contexts in which contraception and abortion have taken place; what women throughout history have done to their bodies to end unwanted pregnancies, and what happens in societies in which abortion is made legal or illegal (a whole map, for example, featured the development of so-called ‘abortion tourism’). The museum also provides an interesting historical overview on the use of contraception, from the earliest recorded in ancient Egypt to the introduction of the pill in the 1960s, and beyond. One can browse through abstracts of hundreds of novels that mention contraception or abortion since the 18th century, and short films from the 1920s until today are used to illustrate the development of attitudes towards sexuality and procreation (interestingly, the 1920s appear more progressive in this respect than some of the modern debates).

The most harrowing part of the museum was a corner set up as a domestic kitchen scene, containing the tell-tale kitchen table on which many illegal abortions took (or still take) place. Next to this table was a strange-looking electrical device which turned out to be the latest invention by the household company Bosch in the 1950s: a precursor of the modern washing machine, called ‘Schallwäscher’, its electrical vibrations were meant to help housewives do the laundry more easily….Bosch, however, was eventually forced to take this device off the market when it turned out that desperate pregnant women would apply what was lovingly called the ‘Waschbär’ to their bellies, causing internal bleeding. What sent an additional chill through our bones was an original 1950’s advertising brochure for the Schallwäscher, casually placed on the kitchen table, which depicted a husband carrying the device and other wrapped-up Christmas presents – the caption saying “This will make her happy”…

Visiting this museum was certainly a highlight, albeit a chilling one. It is unique in tackling a subject heads on that at best divides opinions, at worst sparks violence; a subject that is otherwise politically instrumentalised as, for example, shown in the recent book by Mara Hvistendahl (Unnatural selection, 2011) on birth control programmes in the developing world, including forced abortion and gender selection. However, in this museum, contraception and abortion are elevated to topics that infuse the historical and cultural matrix of countries worldwide and which make the visitor see more than one side of concurrent debates.

Figure 1: A domestic scene from the museum with tell-tale kitchen table. Figure 2: An advertisement for the ‘Schallwäscher’, a precursor of washing machines invented by Bosch; it was taken off the market when it was found out that women applied the electrical device to their pregnant bellies in order to abort. The caption reads ‘Useful in every household’… . Figure 3: Another advertisement with the caption ‘This will make her happy’.

Figure 4: The Frog Test, a biological indicator for pregnancy used until the 1970s. Figure 5: The pill that changed the world. (Images courtesy of MUVS, Vienna)

http://en.muvs.org/

https://www.facebook.com/eMUVS

On Thursday, 14th February, all too soon, it was time to say goodbye to Vienna. Although we had an amazing time, it felt like we left too much unfinished business behind – there was still so much more to see and do! Apart from history of medicine–related museums (some of which are listed below for those interested), one could spend a month in Vienna and visit a different museum each day, or else go to dozens of art galleries, not to forget the world-famous opera houses … Have a look at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_museums_in_Vienna

Anyone planning a visit to Vienna with a special interest in the history of medicine might also want to check out the following:

Sigmund Freud Museum

Vienna Central Cemetery (hosting eminent figures in the history of medicine)

History of Nursing and Medical Care Museum

Museum for Forensic Medicine

Dental Museum, including a replica of a 19th-century dentist’s office .

History of Drugs and Pharmacy Museum

——————————————————————————————————

The unofficial blog for the History of Medicine Field Trip to Vienna.

The group is standing somewhere in Vienna’s city centre, gaping open-mouthed at the beautiful buildings surrounding them (the students are actually panting because Carole is still on inner-city-London-pace).

Carole: This is wonderful. Being here is such an immersive experience. I can’t wait to get to all of the medical history museums, following the path of Mesmer, Lister, Semmelweis….

Student 1: Semmelweis….I’ve heard of that guy!

Carole: …. and seeing the Old Hospital Campus of the late 18th century.

Stephanie: I’m hungry.

Student 2: Is Lister the chap who invented the mouthwash?

Student 3: They had hospitals in the 18th century??

Carole: We must immerse ourselves in the medical history and culture of this place!

Stephanie: Did you know that Vienna is also the ‘Capital of Cake’?

Student 4: It’s snowing; we shouldn’t be out in this weather.

Student 5 (hungover from last night’s visit to the hostel bar): I don’t feel so good.

Carole: Just look at this amazing memorial. It’s huge. I wonder what it’s for. (Shouts) STEPH – what does the guidebook say?

Student 5 edges closer to the memorial.

Stephanie: (reaches for the book and recites): The Plague Column is the best known memorial of Vienna’s city centre. It was erected to commemorate the death of countless plague victims in the last outbreak in 1679. It is said that the plague hit Vienna so hard that the stench of rotting corpses hung over the city for weeks…..

Vomiting noises from behind the memorial.

Carole: Come on folks, we mustn’t be late for our next museum tour. (Runs off with accelerating speed).

Student 4: I can’t move; my feet are frozen to the ground.

Student 6: Where are Carole and Stephanie?

Everybody turns in the direction of a fleeting dust cloud in the far distance. Heads turn in the other direction. Stephanie has spotted a bakery and made a run for it.

[1] Anna Maerker, ‘Florentine anatomical models and the challenge of medical authority in late-eighteenth-century Vienna’, Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 43 (2012), 730-740.

Stephanie Eichberg is a Teaching Fellow at the UCL Centre for the History of Medicine.